By Abdon M. Balde Jr.

THE INVENTION OF BAYBAYIN AND THE ASTILLERO OF PANTAO

My attraction to the town of Libon, Albay came from the 40th stanza of the Ibalong narrative: “El alfabeto fue Sural/ quien curioso combino/ grabandola en piedra Libon/ que pulimento Gapon”.

In translation: “And the alphabet was Sural’s/ Which he curiously combined/ And engraved in stone of Libon/ That Gapon at once refined.”

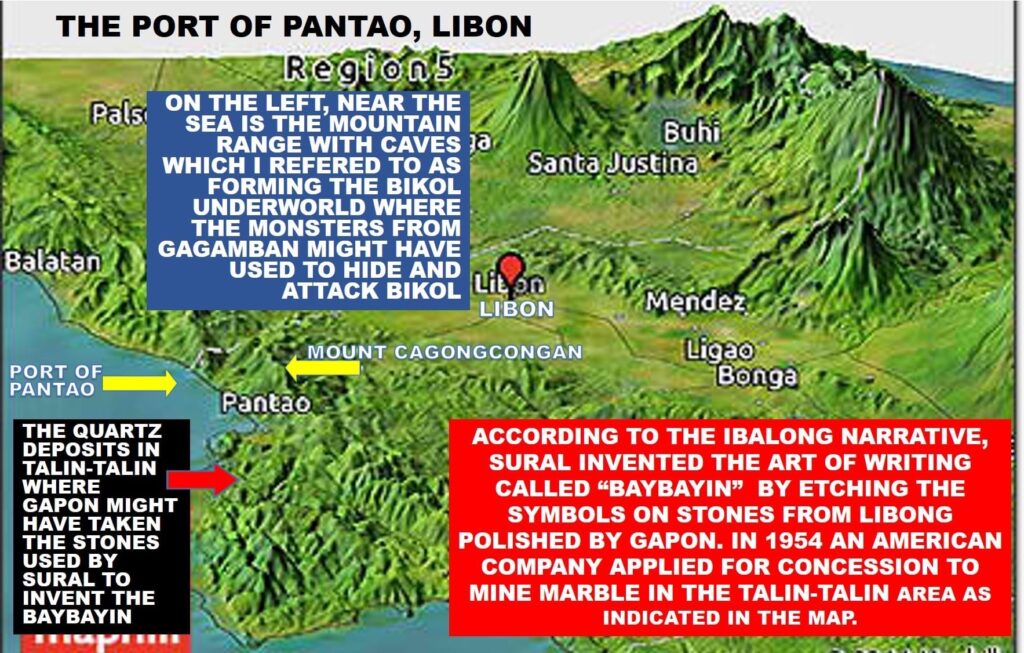

So the system of native writing, which came to be known as “Baybayin” was invented by Sural in Libon? The town is adjacent to Oas, where I was born & where I grew up. In my researches I discovered that in 1954 there was an American company which applied for concessions to mine marble in the area of Talin-talin, on the southern edge of Pantao! But the operation did not push through because the initial explorations revealed limited deposits and most of which were quartz.

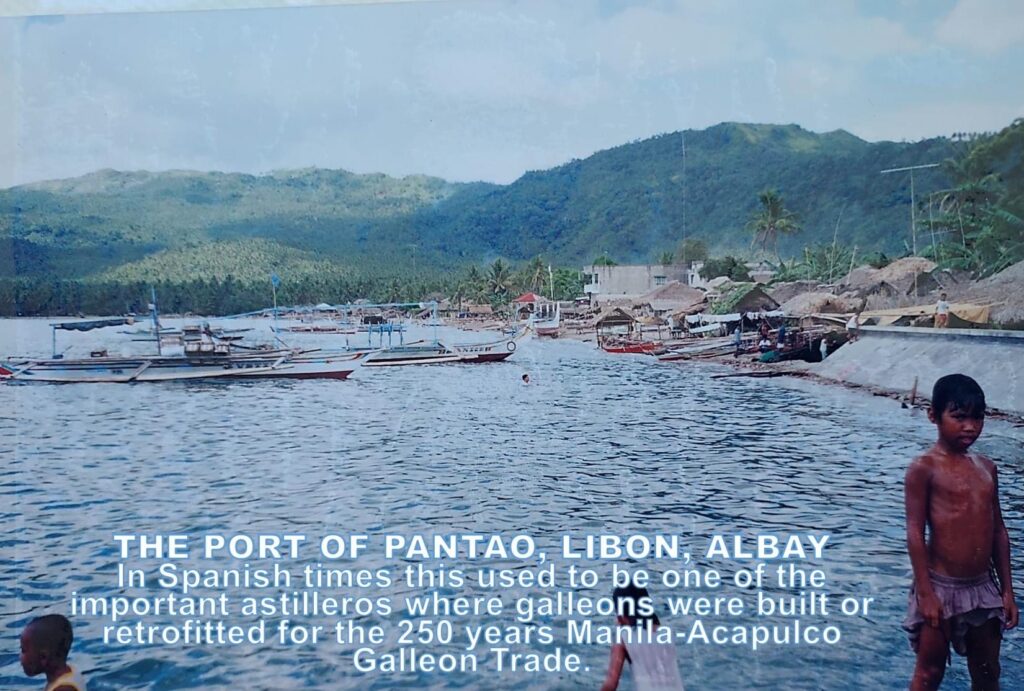

There is another reason: To look for the astillero in Pantao, Libon where some of the largest galleons were made which formed some of the fleet that sailed the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade from 1565 to 1815. The astillero in Pantao was chosen for three reasons: 1) the port is facing the inland sea and was protected from big waves by Burias Island, 2) it is near the San Bernardino Strait which was the exit and entrance of the galleons coming from and going to Manila from the Pacific Ocean, and 3) the abundance in the area of the Philippine molave, a specie of hardwood ideal for building galleons.

In 1667, almost a century before the huge galleon Santisima Trinidad was built in Bagatao, Sorsogon the largest galleon of its time was built in the astillero of Pantao. The galleon was named Nuestra Senora del Buen Socorro. Here was the report of the Agustinian Fray Casimiro Dias on the fateful event: “…that year the galleon Buen Socorro sailed from Albay after it was completed under it Commander Diego de Arevalo and its chief pilot Juan Rodriguez. It sailed August 28, 1667 and was in great danger for it ran aground as it left the harbour; but it was gotten easily by the great energy and skill of the commander. The galleon was the best that was ever built thus far in this islands; and its size, beauty and swiftness were amazing.”

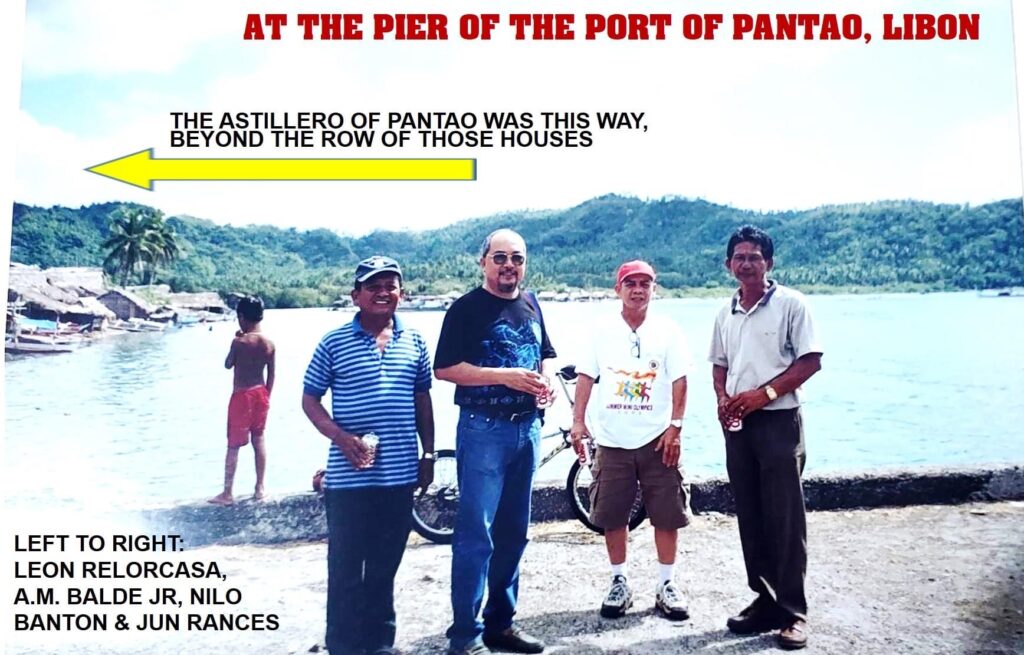

Thus, one day on my second year of research, I fetched my childhood friend Bejamin Rances Jr. who was teaching in Polangui and we set out to visit Libon. “Where are we going?” asked Jun Rances. “To Pantao,” I said. There was a curios look of surprise in his face as he said, “Pantao? Pantao? Kadakul a ba’bu sa agyan pa-Pantao!” (There are so many rats on the way to Pantao!) “Rats” was our euphemism for the NPA rebels in the area. The boundary between Oas and Libon at the time was the sight of many encounters between the military and the rebels since Marcos time and in 2005 some were still known to make sporadic raids of rebels in the area. But I was determined to go, and he relented. “Swertehan man sana katon”, I said. Let fate take its way. And so, I drove my van down the winding and rough 25 kilometers road from the poblacion of Libon down to the Port of Pantao. With me, aside from Jun Rances were my wife Fe and another friend, Nilo O. Banto. After travelling over 20 kilometers I could already see the inland sea. On my left was the mountain range which included Mount Cagongcongan. From the foot of the mountain I saw a wide flat lands extending to the shores of the sea, and I had no doubt in my mind that it was the site of the Astillero de Pantao.

Pantao, even today, is the largest barangay of Libon with a population of 6,767 or over 9 % of the total population of the municipality. It remains to be a fishing village with a port still serviceable to medium size ships that sail towards Matnog, Sorsogon, passes the San Bernardino Strait and on to Allen, Samar. When we reached the poblacion, Jun Rances suggested that we fetch his friend, Leon Relorcasa who came from Oas but now lives in Pantao. The first question I asked Leon was the location of Talin-talin and if there could be a way to visit it. “No way we could go there now,” said Leon, “the sea is rough and it’s a long boat ride from this pier.” Thus, I decided to put off my trip to the alleged mine site.

My next question was, “Do you know the location of the ancient Spanish astillero?” His reply was a blank face. So we walked around the pier, and then to the residential area. There I met an old man who told me an interesting story. He said, when he was young his elders told that during high tides the sea used to reach the foot of Mount Cagongcongan. But the plains are now planted with rice and various crops. Then the old man pointed at the top of the mountain, “See that flat area there? It’s called Kinalayo, because in olden days according to the elders, there burned a fire up there day and night.” I kept silent, but I knew immediately why there was fire up there: Kinalayo was directly above the wide plains that must be the site of the ancient astillero. The fire up there must be the beacon light, and ancient parola or lighthouse, that served as guide for the galleons that entered or left the shipyard. The shipyard was not only for building ships, but for retrofitting ships that have entered or were about to exit the turbulent waters of the San Bernardino Strait. Beyond the San Bernardino was the wide Pacific Ocean.

I left Pantao with a very heavy heart. It was sad that the people there have totally lost the memory of a time when their ancestors were able to rise from being simple farmers and fishermen to become master carpenters and artisans and sailors who made magnificent galleons and sailed the seven seas to foreign lands. Today they return to being tillers of land and builders of small boats because there was no memory keeper, no chronicler or writer among them to remind them of their rich heritage. Sad.