Aside from being an archeological landscape holding thousands of pre-colonial relics, including the Ticao gold spike teeth, the human face rock statues, burial jars with different patterns and sizes, jade beads, and the infamous Baybayin-inscripted Rizal Stone and the ecological frontier for the conservation of Manta Rays, Ticao Island is now also becoming more active to introduce their creative identity.

On the day of the patronal fiesta of the heart of Ticao, Museo de Ticao Working Group, together with the tourism offices of the Municipality of San Jacinto, and Monreal, humbly opened to the public Museo De Ticao which sits at the Pasalubong Center, steps away from the busy port of San Jacinto.

It took me an acceptable 30-minute motorcycle ride to reach the museum. Some police officer pointed me to an almost ceiling to floor glass door with blue and white balloons pitched on its either side. The gentle hum of people’s voices grew clear and understandable as I opened the door. The usherettes in navy blue shirts greeted me with a smile, “Welcome to Museo De Ticao,” they’d say. Sitting between them was a logbook for visitors. I write my name and my municipal address and wander my eyes. One of the usherettes then gave me a small blue sticker saying “PAGLAOM exhibit, the inception of Museo De Ticao” which you could stick to your clothes’ breasts.

The place was small yet solemnly warm. Playing in the background is a hugging classical music, traveling to and fro in the room, serene and expensive. It has a pleasant and soothing ambience. The place was buzzed by dignitaries, artists, people from the LGU, and local guests, even the Mayor of San Jacinto Francesco Altarejos in simple blue shirt and jeans attended himself. As I walked through the galleries, Architect Rhodiebert Nuevo, the exhibit assistant and set designer approached me and shaked my hands and introduced me to curator of the exhibit, Miss Catherine Villamor as we talked briefly on the context of the museum and its plans in the future.

This interesting exhibit was actually divided into three interesting showrooms; Lingion (to look back), Isulong (Progress), Atamanon (Nurture).

LINGION. I saw big installations of art from Ticaonon visual artists including tattoo artist Ronnie Barrun’s bright oil canvases; Czar Espenilla’s Galleon Trade, Espenilla is a well-known string artist in San Jacinto; and Lealda Villamor Antonio’s paintings on her childhood life in Ticao, she also chairs the group behind the museum.

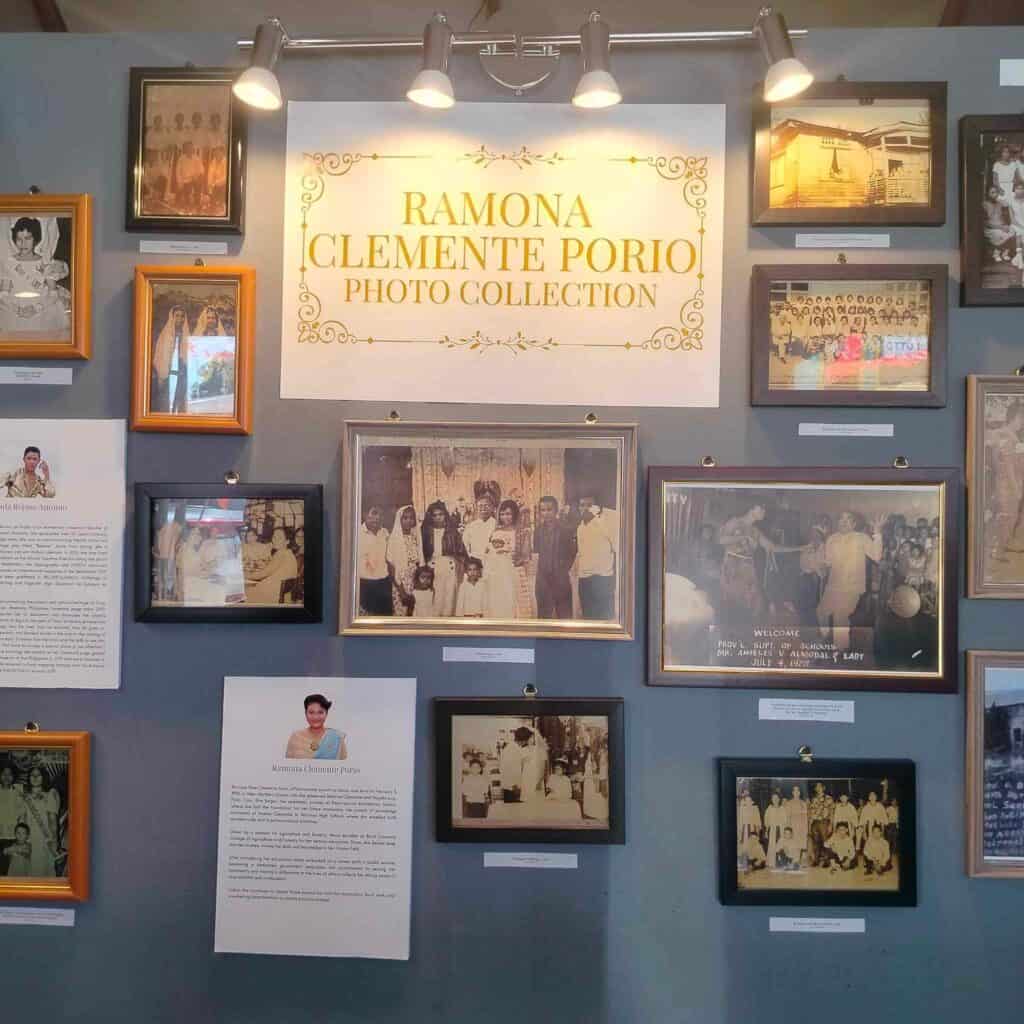

The main hall tent side by side hundreds of unseen old photographs that seemed to be generously allowed by the remaining families of photo collectors to be showcased in public. As my eyes landed to every frame, they looked like frozen windows of the past, a glimpse of what was once alive and thriving, that there was life on an island even before the 21st century.

Anyone visiting the museum could be lost in the fog of those windows, and get a glimpse on the life of early settlers of the island, what kind of town it was, what kinds of families live there, what were their daily routines, what kind of livelihoods they had, what occasions they used to celebrate, and the type of traditions and culture people back then have that we still carry today. It was far from what people used to connote that ancient Islanders were ignorant, confused, and had no history to tell its own.

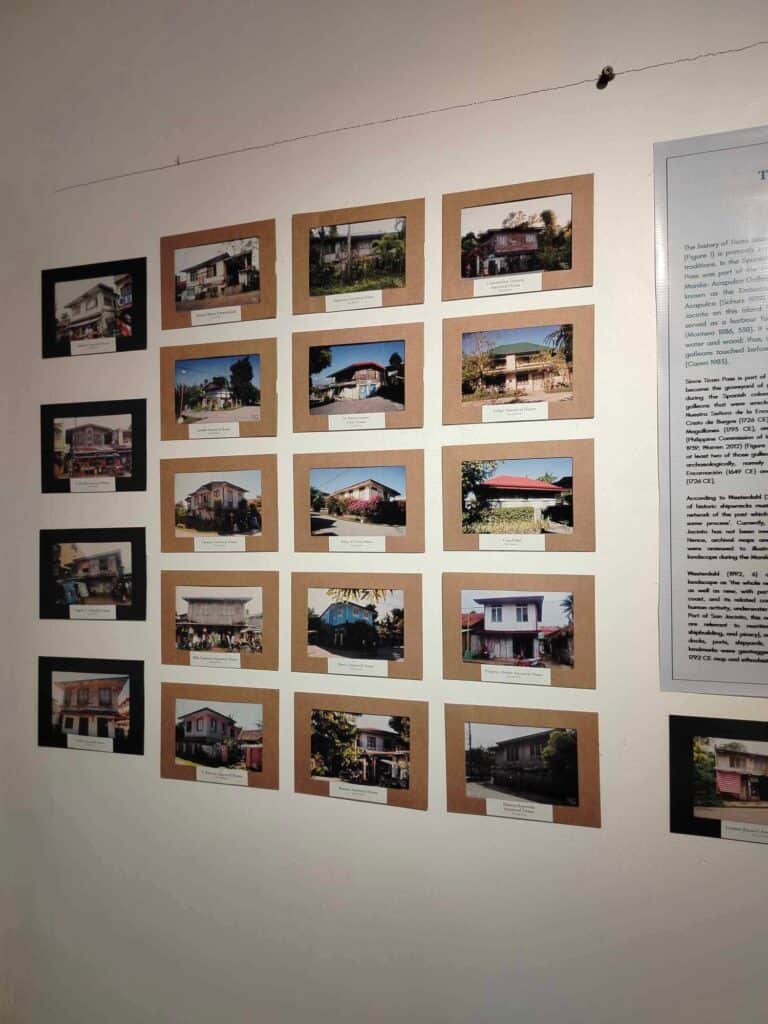

ATAMANON. In one corner of the gallery were photographs of ancestral houses in Ticao. A play in the imagination would tell you that these houses were not only older than us but also were witness to events that come from several generations. They remained untouched while the world around them kept on changing. As old as our history, the very history we failed to remember and continuously forget.

In the same corner were photographs of beautiful landmarks and most-visited tourist destinations on our island. They were colorful and vibrant in contrast to the old photographs in the main hallway. On the same wall was Ryan Leico Faura’s nostalgic essay on Fireflies. Reading the said essay was a tug to my heart, especially that a recent award-winning Metro Manila Film Festival entry called ‘Firefly’ had just mapped our island nationally because of the magical fireflies in a mystical cave in Ticao.

ISULONG. I read essays on the strategic waters of Ticao pass during the colonial period and its involvement in the famous Galleon Trade. Catherine Villamor, a historian-archeologist, and the curator of the exhibit also presented archeological projects such as excavations and underwater archeology investigation of the wreck galleon Santo Cristo De Burgos that sank in Ticao Pass in 1726, the excavations and archeological findings by the National Museum of the Philippines encourage Museo De Ticao working group that it is high-time to establish a local museum in the island.

Inside the Museo de Ticao, local products such as Batuan jams, handicrafts, brochures, pasalubong t-shirts, and the likes were offered.

I stopped. Scanned the whole room. I had never seen Ticao Island from this angle. For the first time, it made me proud to be in this space, surrounded by the evidence of my rich roots as a Ticaoeño.

The Paglaom exhibit runs from May 1-4. Paglaom is a Visayan term that means “hope,” which beautifully captures the spirit of the display. Museo de Ticao is a promising act of protecting and unveiling the cultural and art legacy long buried in Ticao Island.

“It started as an idea I brought up by numerous discussions and presentations to people I knew who hailed from San Jacinto, initially, and then branched out to other friends, classmates, relatives in other towns. Some of them were living overseas. This was June 2023,” Lealda Villamor-Antonio, chairperson of Museo de Ticao, said.

“I had this thought because I traveled to several countries and I visited different museums—in major cities like Louvre in France, British museum, Prado, MoMa, etc. apart from the big ones I also saw museums in the outskirts, [for] example in Salta Argentina, in Ethiopia in Africa. In the barrios or in liblib. But they have a museum.Most of the museums I saw are attached to the old church. The San Jacinto Church is as historical as I knew. So the idea crystallized more,” she added.

Museo de Ticao will not only be one museum but a network of museums?

According to Catherine Villamor, the curator of Museo De Ticao, they are planning to install satellite museums of Museo De Ticao in three other municipalities: Monreal, San Fernando, and Batuan, respectively.

Catherine unveiled that the planned site for the museum building was next to the new municipal hall in Barangay Burgos, San Jacinto. As of now, Museo de Ticao is situated at the Pasalubong Center, and the exhibit room is set to expand after the Dayaw Dalan Festival.

The group behind the museum initiative is still doing fundraising campaigns for the museum and would like to have the support of the LGUs of the municipalities in Ticao Island.

“We are not really asking for monetary or financial support but more on the support of the community. We will be more inspired to raise funds, at the same time, for funding institutions to be inspired to fund us to see the impact of this in our community to preserve, protect, and promote our natural and cultural heritage,” Catherine said.

As I leave the place, the experience feels surreal. Never in my wildest dreams had I imagined a museum on my island, yet it is finally here. Although I was afraid that this would only be a spark in the dark, talking to Ticaonon artists, people behind the initiative, and the curator herself, I began to hope—bigla ako napalaóm. This is what happens when the best of the best comes back to our island and chooses to give back to our community instead of leaving it brain-drained. This is what happens when a group of people or a single person starts to hope again for their community. Through art and culture, the Museo de Ticao is truly a beacon of hope for Ticaoeños. | Mera Melitante