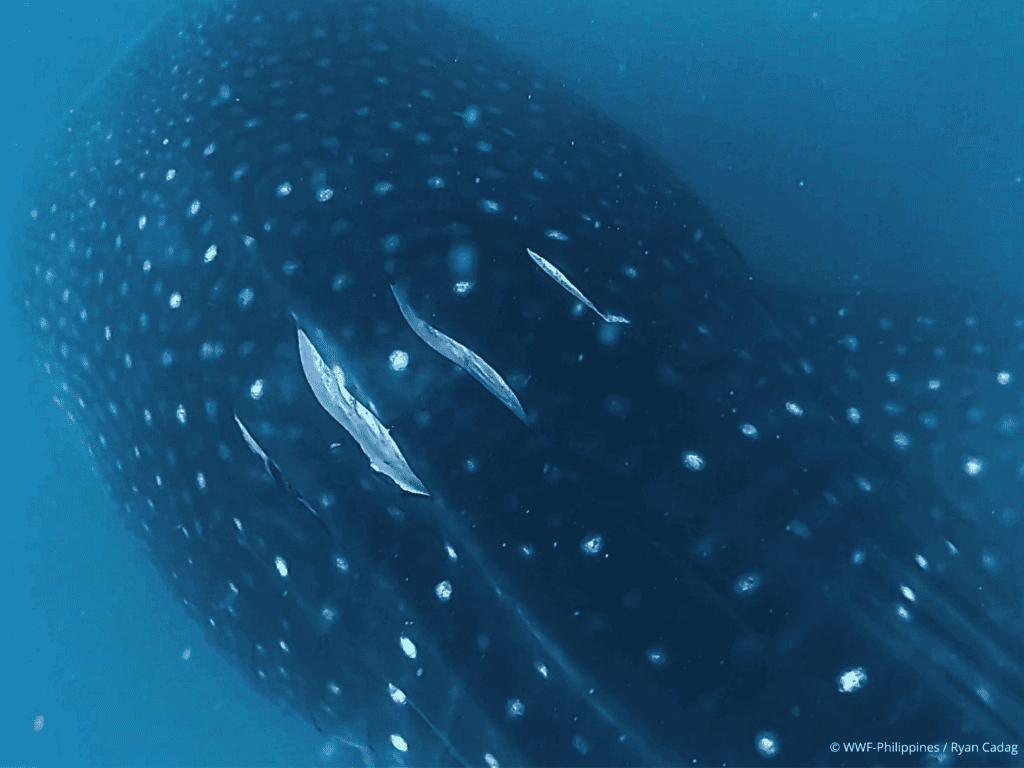

Over the past three years, whale shark sighting data by the World Wide Fund (WWF) for Nature Philippines has decreased. There were 58 whale sharks in the year 2021, 57 in 2022, and only 43 in 2023, indicating a three-year downward trend in their population.

From January to June, whale sharks are frequent in the waters around Donsol—the “butanding” capital of the Philippines—with the peak season for interactions occurring between March and May. While this period offers the highest likelihood of encountering whale sharks, there is no absolute guarantee due to their unpredictable behavior in their natural habitat.

The dwindling and increase of individual butanding still cannot be determined and are still ongoing studies as there are many factors affecting the lives of species in water biodiversity.

Recently in Donsol, a reported whale shark was found with its left pectoral fin trapped in fishing gear, showing the threats posed by plastic waste and improper fishing practices as two of many factors that can affect the behavior of whale sharks and other species like sea turtles or “pawikan.”

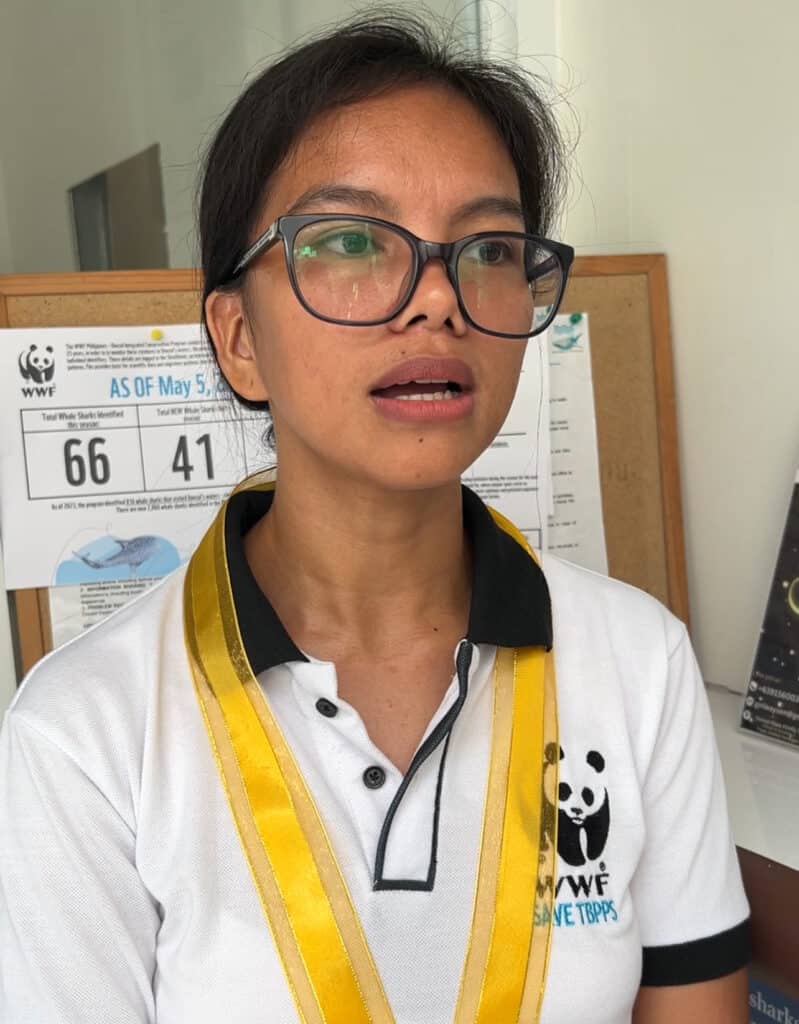

Andrea Pimentel-Paz, 31, the project manager for mangrove ecosystem management at WWF, noted that despite the uncertainties surrounding the whale shark population dynamics, the community remains committed to safeguarding their habitat.

The dwindling of the butanding sightings in Donsol and the emergence of the pandemic not only affect ocean biodiversity but also the community.

“Walang eksaktong solusyon kung paano mapataas ang population, pero we have to do a collective effort, collaboration, and integration of our responsibility to protect our natural resources, especially our coastal resources, to ensure na kahit kaunti ang population regardless kung kaunti siya or marami at least pumupunta pa rin ang mga butanding dito sa Donsol, at dahil rin ito sa maayos na pamamalakad ng local government of Donsol,” Paz said.

Waves of initiatives

A “ridge-to-reef approach” is a holistic environmental management approach that focuses on the relationship of the ecosystem on the highlands (ridges) to the coastal and marine areas (reefs), which means that what people do on the mainland will affect the water biodiversity and the species living on it. Initiatives by WWF, which began in Donsol in 1998, have expanded significantly.

In collaboration with local leaders and stakeholders, WWF initiated a community-based whale shark ecotourism program. This program not only established guidelines for the protection of the species but also generated new tourism employment opportunities for locals.

Nyx Bailon, Communications Officer of the WWF Donsol Integrated Conservation Program, emphasized the organization’s holistic strategy, which extends beyond marine ecosystems to include community engagement and education.

One key initiative in Donsol is the Nakamoto Project. Nakamoto meaning Nakamotor, the project involves the collection of waste from remote barangays using motorcycles. “The Nakamoto Project collects waste from areas unreachable by traditional trucks,” explained Bailon. This initiative ensures that waste, especially laminated plastics, does not end up in the ocean. The project exemplifies community involvement in environmental conservation and addresses the logistical challenges of waste management in remote areas.

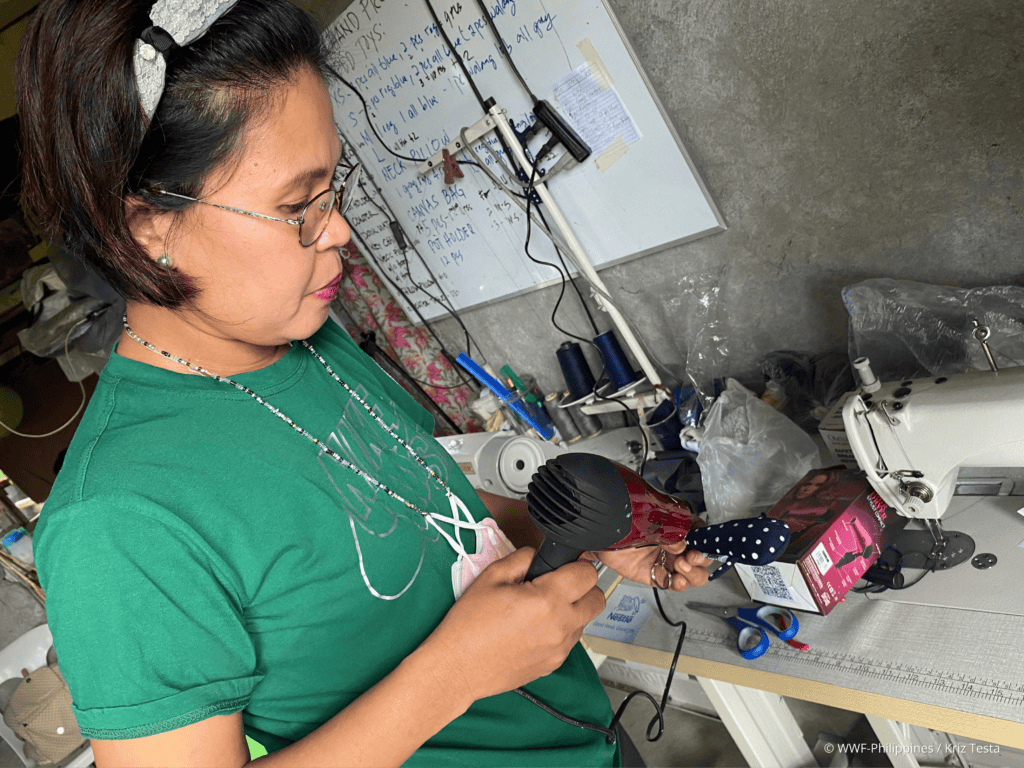

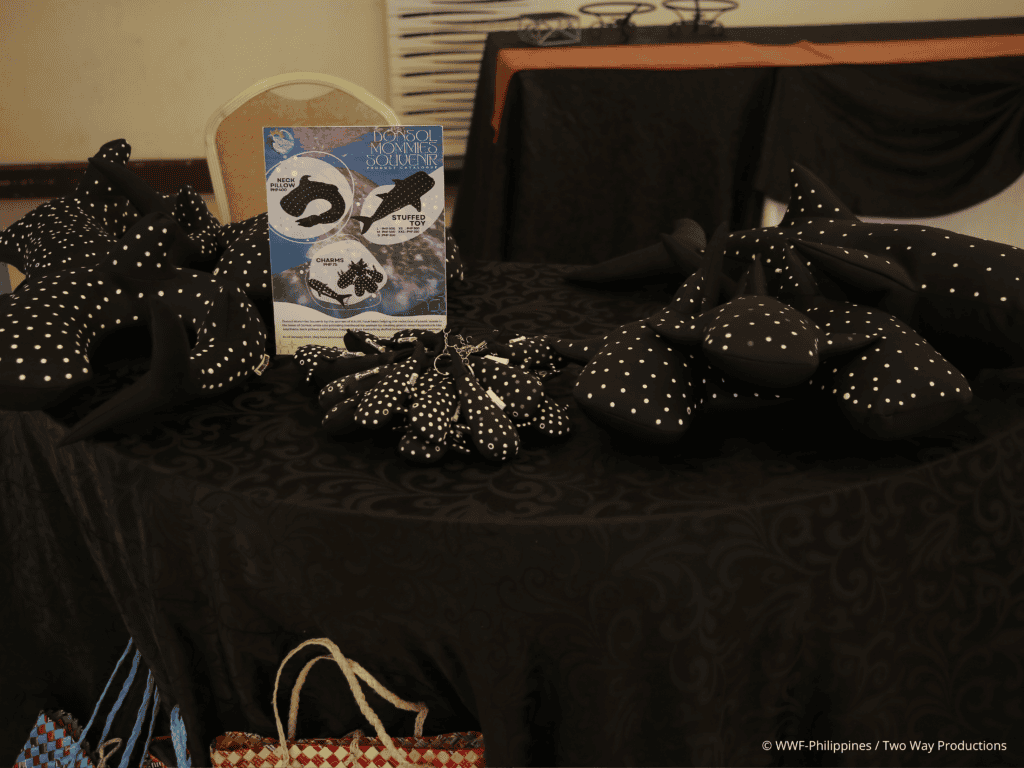

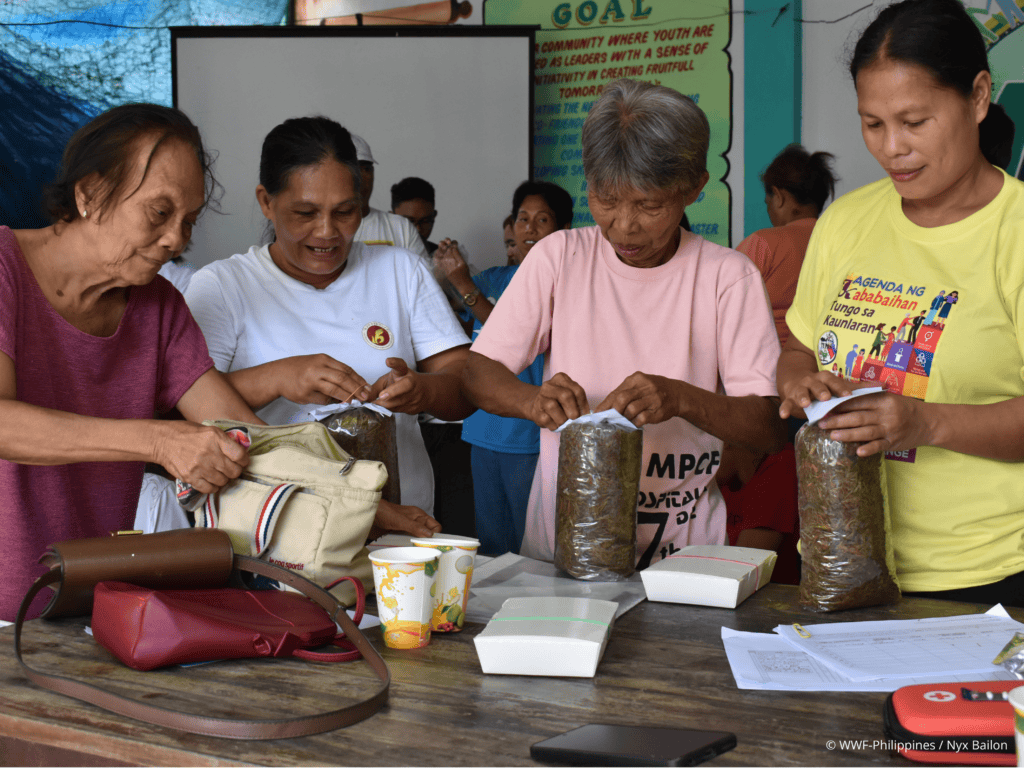

The collected waste from the Nakamoto Project is repurposed through the Kalipi Plushie Project. The women’s group Kalipi transforms the laminated plastics into plush whale shark toys, which are stuffed with the collected plastic waste. “Instead of the waste ending up in the sea, it becomes a tourism product for Donsol,” Bailon highlighted. The plush toys have gained national recognition, winning two awards, and serve as a sustainable and creative solution to waste management. WWF played a pivotal role in establishing this brand, demonstrating a successful model of community-driven biodiversity conservation.

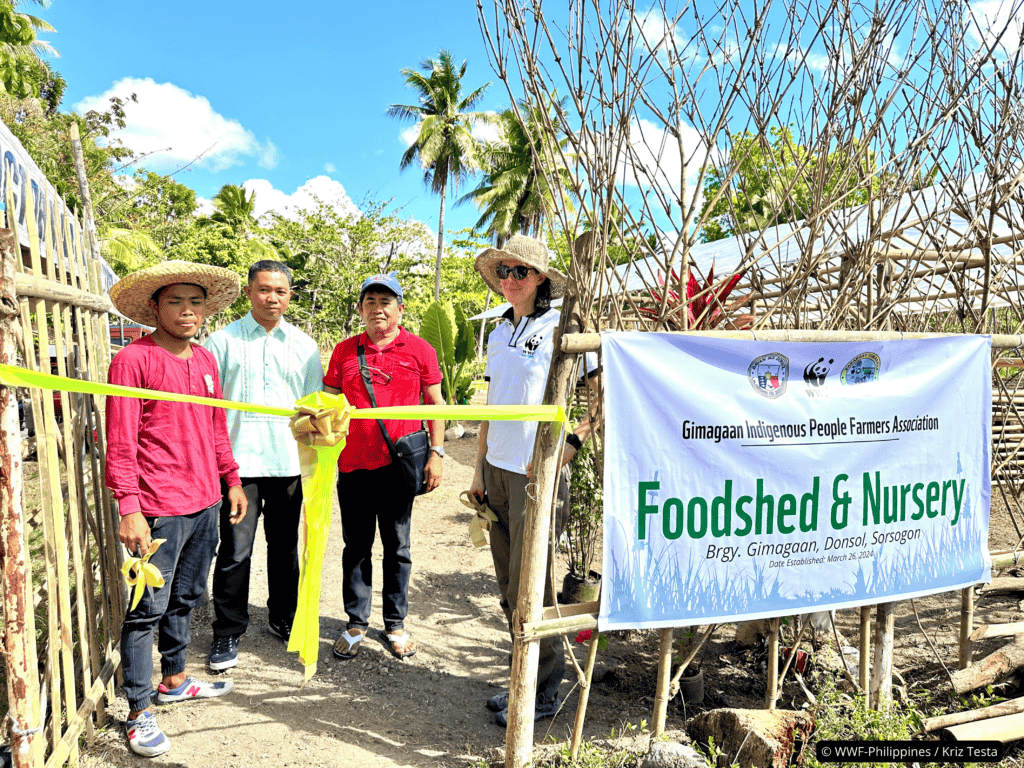

WWF also supports the Indigenous Peoples (IP) communities in Donsol, the Agta Cimarron and Agta Tabangnon tribes. “We conducted free and prior informed consent before starting any activities in their ancestral domain,” Bailon noted. “The IP community requested help in developing biodiversity-friendly enterprises to benefit from and conserve their resources.”

Through these integrated efforts, WWF’s ridge to reef program exemplifies a sustainable model for conserving marine biodiversity while empowering local communities.

Ticao-Burias Pass Protected Seascape

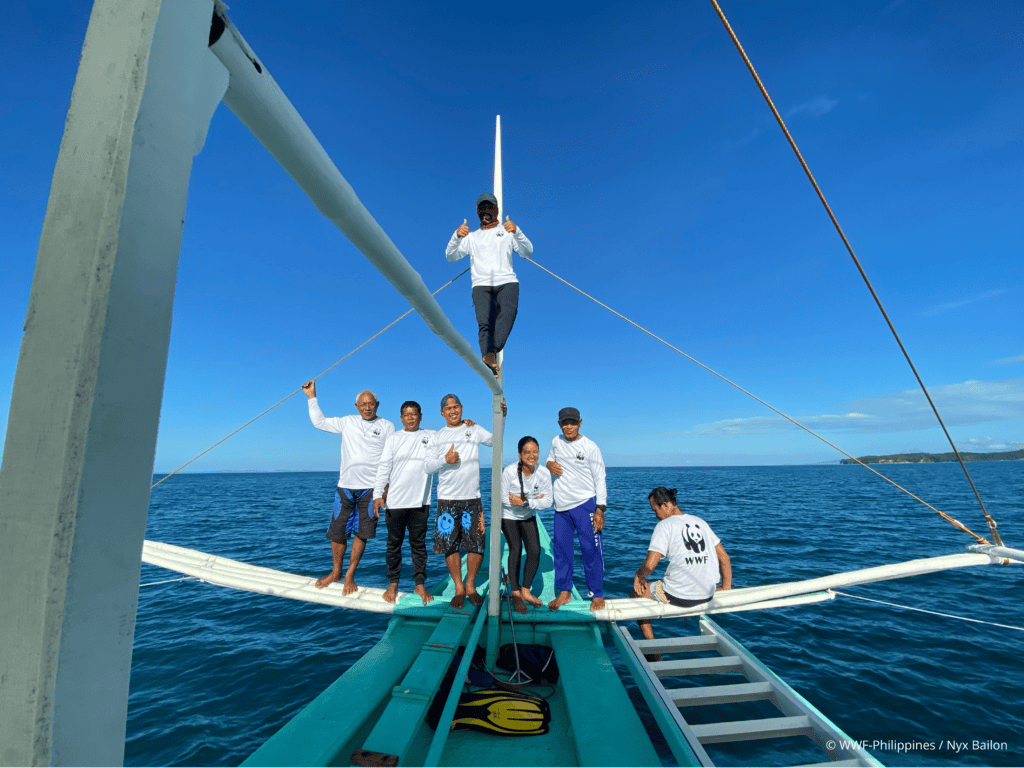

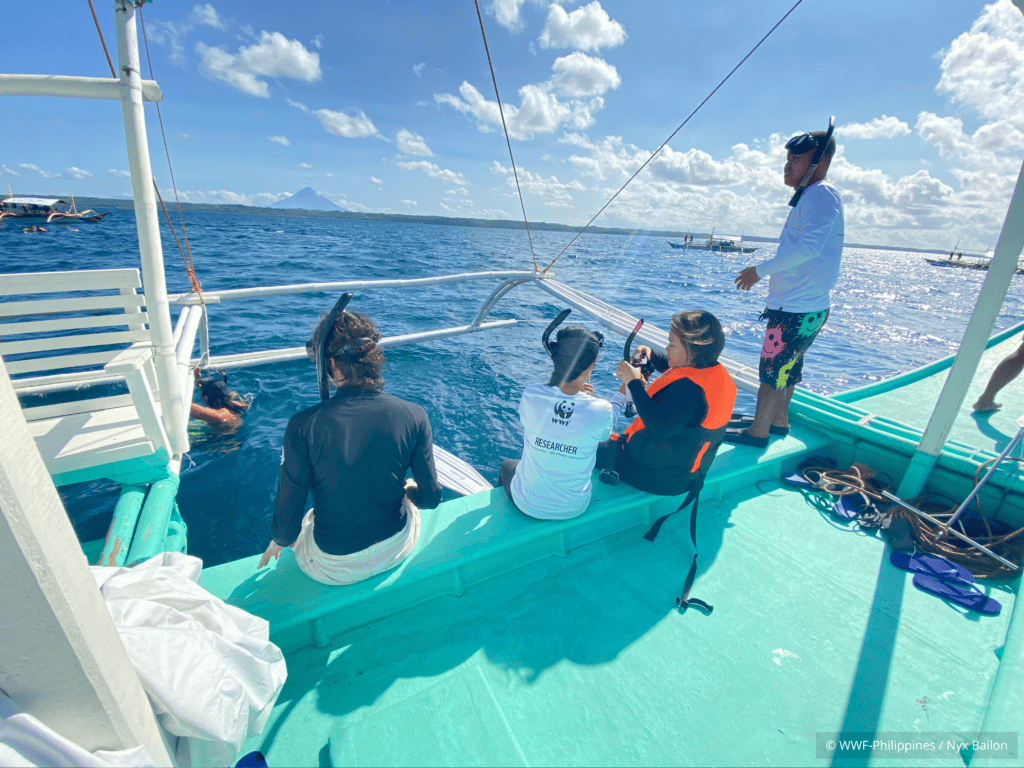

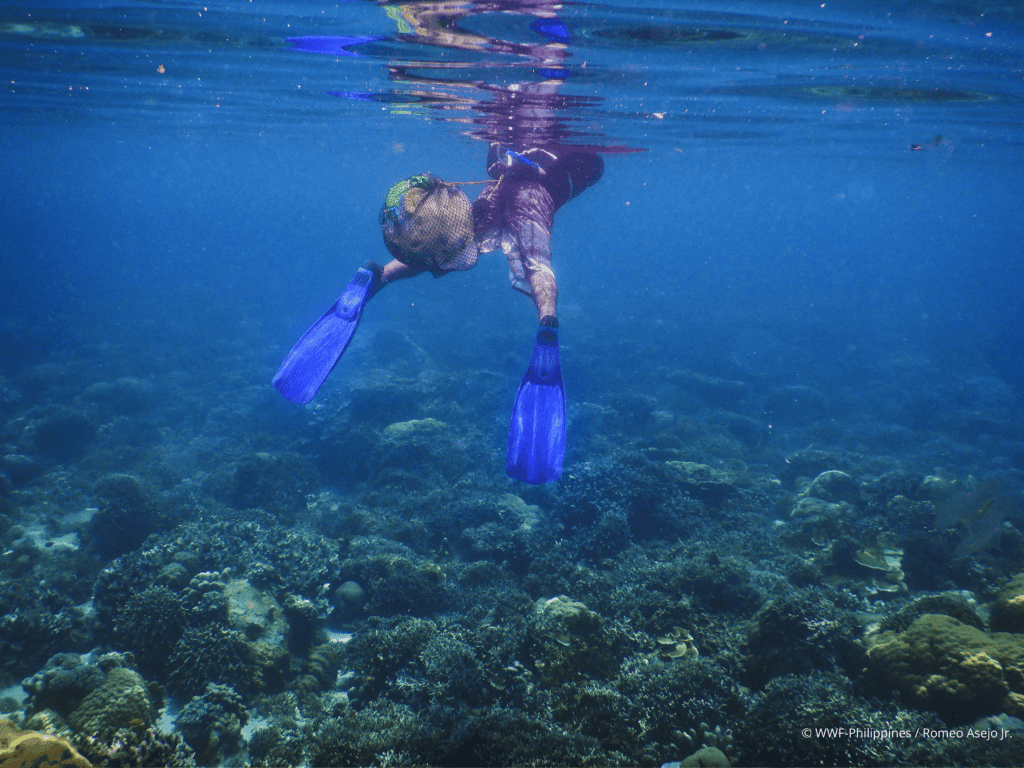

WWF scientists study the behavior and migrations of whale sharks by identifying and tracking them. The integration of community and conservation is evident in the efforts to manage waste and protect marine life.

The organization now covers the entire Ticao-Burias Pass Protected Seascape (TBPPS), in implementing projects like seasonal whale shark monitoring, mangrove rehabilitation, and plastic reduction campaigns.

“Isa sa aming mga projects ay ang mangrove rehabilitation. Kasi ‘yong mangrove [are the] reasons why our coastal seas or our marine resources are still productive, nag co-contribute sila. ‘Highlands to oceans, ridge to reef,’ kung ano nangyayari sa tao ay apektado ‘yong dagat and very evident ‘yan sa waste disposal…bumabagsak ‘yan sa dagat, and the goal of the project is also to lessen the plastic,” Paz said.

WWF-Philippines has been working with the local government of Donsol and the Department of Tourism (DOT) to protect the local whale shark population. Employing a landscape approach, WWF-Philippines and its local partners aim to minimize human pressures threatening the health of the Ticao-Burias Pass.

The conservation organization also helps operate a citizen science effort to keep track of whale sharks passing through the protected seascape. By tasking visiting tourists with documenting and sharing the whale sharks they identify while out on guided tours, WWF-Philippines has helped create employment for locals while developing a database of individual whale sharks that have passed through the area over the years. .

Local stakeholders, including the Butanding Boat Operators Association (BBOA), face daily challenges but remain resilient. Enhancements in boat operations and adherence to regulations have contributed to the town’s tourism boom. With 59 registered members, the association plays a pivotal role in ensuring safe and sustainable whale shark interactions. Moreover, the local government unit (LGU) of Donsol, in collaboration with the WWF, is dedicated to research and protection efforts.

The coastal waters of Donsol are designated as a whale shark sanctuary, with regulated fishing activities to ensure a safe habitat for the Butanding. WWF’s approach also involves non-invasive photo identification of whale sharks and engaging volunteers and tourists in citizen science.

This initiative not only helps track whale shark movements but also provides employment opportunities for locals. The Ticao-Burias Pass Protected Seascape (TBPPS), a biodiversity hotspot, benefits immensely from these conservation efforts.

The aftermath of collective efforts

Paz highlighted that 66 whale sharks have been identified in Donsol this season for the month of May, a considerable increase from the 43 individuals spotted last year. Of these, 41 are new sightings, while the rest are resightings.

Donsol serves as a crucial feeding ground, rich in plankton and small fish, essential for the butanding’s sustenance. The place continues to attract tourists, and the combined efforts of local communities, conservationists, and government entities demonstrate a successful model of eco-tourism.

By preserving the natural habitat of whale sharks and promoting sustainable tourism practices, Donsol stands as a beacon of hope for conservation and community development.

The journey ahead requires sustained commitment and collaboration, ensuring that Donsol remains a sanctuary for whale sharks and a thriving destination for eco-conscious travelers.

Through education, responsible tourism, and continuous conservation efforts, the town of Donsol not only safeguards its marine treasures but also secures a prosperous future for its community.

Don Llagas, the town’s tourism officer, said that Donsol witnessed an 80 percent rise in tourist numbers compared to last year, with 24,000 guests in March alone. This surge is not only a testament to the uniqueness of these gentle giants but also to the robust and collaborative conservation efforts in place.

“We are just fortunate, dahil sa taon na ito ay malaki ang increase po lalong lalo na po sa ating mga, sa number ng ating mga tourist, international and local guest. Kung last year nasa 30 percent lang po ngayon po ay lumaki ng 80 percent, and sobrang blessed kami na patuloy na bumabalik na po ang ating mahal na turista sa bayan ng Donsol. Just like the last month of March, we had 24,000 guests from accredited and non-accredited accommodation establishments,” Llagas shared.

As the world’s largest living fish in the sea, whale sharks can reach lengths of up to 12 meters and weigh as much as 21 tons. With mouths opening as wide as 4 feet, they are the only shark species that feed on plankton and other small prey like crustaceans, fish, or squid.

Paz believes that collective effort will create a big impact on biodiversity, as she encourages not only people in Donsol but also individuals to practice simple ways that can create a big impact, especially being cautious about what you trash everywhere, as it may end up in the sea, affecting marine biodiversity. I Aireen Perol-Jaymalin, Alliah Jane Babila

Photos by: WWF