In Masbate, women are tackling problems they didn’t cause—from hauling water from long distances to recycling waste. Their efforts are vital, but how long can communities like theirs carry the weight of lack of basic services in a warming world?

MONREAL, Masbate—In the village of Real in this town on Ticao Island, women like Amalia Bartolay begin their day hauling buckets of water to keep their backyard gardens alive.

With solar-powered tanks often running dry and manual pumps requiring extra effort, the task becomes even more grueling when the nearest water source is a 30-minute walk away.

“I run out of breath when I bring water to this vegetable garden,” Bartolay told BicoldotPH, pointing to the half-full drum at higher elevation. “During hot days, the spring we rely on can’t meet the plants’ needs.”

For Bartolay and the 50 members of the Real Women’s Organization, growing food isn’t just a way to earn. It’s a lifeline in the face of deepening droughts, unreliable infrastructure, and scarce employment, all exacerbated by climate change.

NGO support

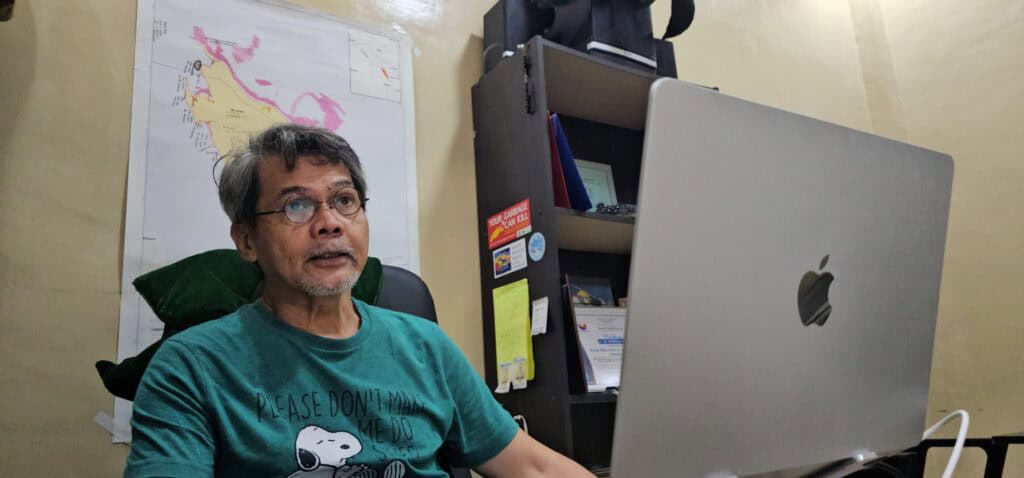

On Aug. 18, Bartolay and 14 other members of their organization raised their concerns to Kevin Ricafort, livelihood officer of the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) Philippines. The group is a beneficiary of WWF’s foodshed program, which aims to provide sustainable food sources to vulnerable communities.

“Most municipalities have women’s organizations,” Ricafort said. “We choose those with the capacity and commitment to sustain the project.”

The organization manages two vegetable gardens in Real, a village that is also home to the Matang-Tubig Watershed Forest Reserve. Despite being surrounded by water sources, all seven puroks (zones) in the village face water scarcity.

“They say we have an abundance of water, but the people remain thirsty,” said Jonna Espinosa Ubaldo, 51, the group’s president. Ubaldo and other members of the organization said that only Real village has problems with water. “What we need is water piped directly to our homes.”

They said that during elections, the water distribution becomes an issue, but the discussions do not materialize into projects.

Aside from drought, Real Women’s Organization also deals with pests that make farming harder. They have since observed higher prevalence of pests in recent years.

Matang-Tubig, a protected area since 1994, feeds into the Ticao-Burias Pass Protected Seascape, the second largest marine protected area in the Philippines. It once supplied water to the village’s zones via a pump installed by the Department of Social Welfare and Development’s Kalahi-CIDSS program.

But when tubes were installed directly into the spring, the water flow declined, leading the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) to prohibit the setup. This decision, while rooted in environmental protection, underscores a painful irony: even as access to clean water has been recognized as a basic human right since 2010, communities like Real continue to struggle for it.

The DENR’s Protected Area Management Board (PAMB) oversees watershed protection nationwide.

There’s also the intensifying climate pressures, which according to the World Risk Report by Bündnis Entwicklung Hilft can prolong drought, risking access to clean water for 2.2 billion people worldwide. The same report warned that the Philippines has ranked as the most climate-vulnerable country globally for three consecutive years since 2022.

In Bicol, the effects are already being felt. During April and May this year, heat waves reached “dangerous levels,” according to the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical, and Astronomical Services Administration (Pagasa), drying up springs and straining communities that rely on them for farming, drinking, and daily survival.

Livelihood, resistance

The 50 members of the Real Women’s Organization created the vegetable gardens as a response to livelihood challenges. With many husbands working as farmers or construction workers in Metro Manila, the women sought ways to support their households and community.

“In these difficult times, with children still going to school, it’s really important to be able to provide support in any way possible,” Ubaldo said.

The gardens now supply fresh vegetables like eggplants, beans, tomatoes, and bitter melon. These produce previously had to be sourced from San Jacinto, a neighboring town 45 minutes away by motorbike.

“We sell fresh and inexpensive vegetables,” Ubaldo said. “Before, we had to buy from San Jacinto because there were very few vegetable farmers here.”

With water still a challenge, the group rotates watering duties and continues learning about climate-adaptive planting schedules.

“Women’s roles in the fight against the climate crisis are very important,” Ricafort said. “In a household, it’s the mother who teaches the kids.”

Studies show women and children are disproportionately impacted by climate change. During droughts and erratic rainfall, rural women walk farther, work harder, and face increased risks, including gender-based violence.

Confronting plastic, too

The burden doesn’t end with water and food.

In Monreal’s coastal barangays, women are also on the frontlines of another crisis they didn’t cause: plastic pollution.

In Famosa village, mangroves are choking on waste that locals believe drifts in from outside Ticao Island.

To fight back, the local government unit (LGU) launched a rice-for-plastic program, encouraging residents to collect trash in exchange for food. The Real Women’s Organization helps turn this waste into eco-bricks, building fences from discarded packaging. But even these efforts highlight a deeper imbalance.

“The law doesn’t clearly define the role of LGUs,” said WWF’s Manuel Narvadez Jr., referring to the Extended Producer Responsibility Act. “They should be central to implementation because they’re on the ground.”

Without clear support, communities like Real are left to manage the fallout, whether it’s plastic in mangroves, microplastics in seafood, and rising risks to health and biodiversity. A WWF study in Donsol confirmed microplastics in coastal waters, and researchers believe the entire Ticao-Burias Pass is affected.

“They don’t dissolve. Organisms can’t digest them,” marine pollution expert Mark Ariel Malto told BicoldotPH through a Zoom interview. “Through biomagnification, the toxic effects move up the chain.”

Malto’s research found microplastics near mangrove estuaries just 20 kilometers from Monreal, threatening the very ecosystems that women rely on for food and protection. His warning is clear: even small pieces of plastic can enter the food chain, and eventually, human bloodstreams.

“Smaller organisms are affected first. But through trophic cascades, their predators suffer too.”

Funding disclosure: This work was supported by WAN-IFRA Women in News. This story reflects the author’s perspective and not those of WAN-IFRA Women in News.