By the 1990s, the sea off Barangay Nursery in Masbate City seemed endlessly generous. Fishers like Jojo Soria reeled in groupers, buraw (mackerel), and mormol (parrotfish) with ease. But its bounty was taken for granted.

Sustainability was a foreign word, and cyanide or dynamite simply meant faster fishing.

“Catch fast, earn fast. That was the mindset,” Soria reflects.

Yet beneath the waves, damage steadily accumulated. By the early 2000s, Masbate City’s municipal waters were in crisis: fish stocks collapsed, coral reefs crumbled, and desperation drove fishers further into destructive practices.

It was only when the city government intervened that the tides began to shift.

A sanctuary born

On Oct. 24, 2002, the degraded waters off the villages of Nursery and Tugbo were officially declared the Buntod Reef Marine Sanctuary. The 250-hectare stretch of coral reefs, mangroves, and sandbar became a fragile source of hope for marine life and a fishing community of over 28,000 people then grappling with the aftermath of environmental neglect.

For Soria and his peers, it marked a turning point.

Those who once exploited the reef were invited into a new role: protectors. Organized into an association, they became bantay dagat (sea patrols), sworn to safeguard the sanctuary they had once helped destroy.

“We used to go against the government. But we’ve been reformed,” Soria said.

Their group, the Samahan ng Mangingisda ng Puro Sinalikway (Samapusi), emerged not only as a symbol of reform, but also as a foundation of community resilience.

Reform and recognition

According to Jofer Asilum’s 2019 study, the Buntod Marine Protected Area has become central to local development. Ecological gains have directly benefited fisherfolk, especially Samapusi, now a recognized people’s organization.

The group’s transformation into an ecotourism provider reflects the power of sustained organizing and institutional backing. With support from a 2015 Memorandum of Agreement with the City Government, Department of Environment and Natural Resources Bicol, and Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources, members received training, livelihood aid, and formal recognition as marine stewards.

These investments turned Buntod into both a sanctuary and a thriving tourism hub, while also improving the lives of Samapusi members by enabling them to send their children to college and purchase household necessities.

But Asilum also documented stark disparities in Tugbo which also “rely on the ecosystem services of the MPA.”

While Samupasi of Barangay Nursery managed the MPA as an established people’s organization, Tugbo’s fisherfolk were just beginning to organize, leaving them with limited capacity to assert their rights. This gap fueled uneven access to support and heightened exposure to external stressors like the oil-fired power plant in nearby Mobo town.

“The MPA’s core zone’s no fishing policy also forced them to fish in far waters,” Asilum noted.

He cautioned that without comparable aid, the community risked deepening marginalization, especially after losing nearby traditional fishing grounds to power plant activities, which fisherfolk claimed to have disrupted local biodiversity.

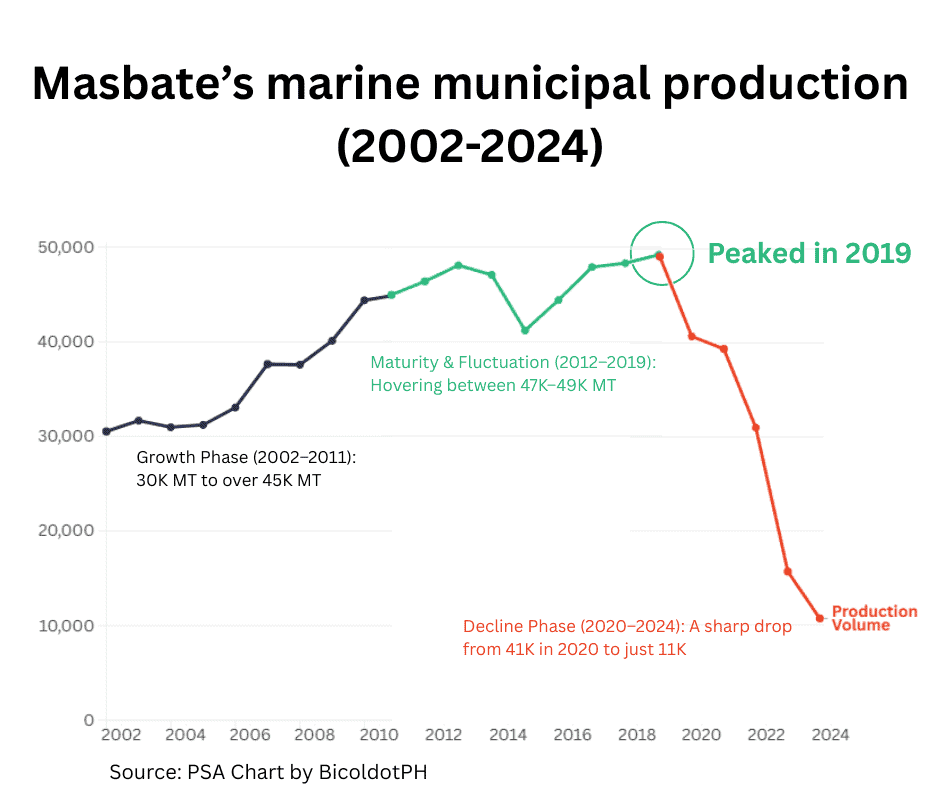

Masbate Province, the leading municipal fish producer in the Bicol Region and home to one of the country’s major fishing grounds, is facing a worrying decline in output. This drop reflects wider issues like illegal fishing and coastal degradation, threatening food security and livelihoods.

Masbate ‘s marine production plummeted by 74% from 2020 to 2024, sounding the alarm on the province’s ecological strain.

From nets to patrols

Today, Samapusi stands as the sole accredited ecotourism provider in Buntod.

Members patrol its waters, educate tourists, and manage conservation efforts. Through the Integrated Coastal Resources Management Project (ICRMP), they joined coral transplantation programs, restoring broken reefs with new growth.

Annual mangrove planting efforts reinforce coastal resilience, focusing on bakauan-bato, a species valued for its thick root network and ecological importance. The bantay dagat persist with dedication, even if the survival rate is only about 20 percent of the estimated 5,000 propagules.

Even fallen mangrove leaves nourish life, breaking down into organic matter that sustains plankton and juvenile fish. These interconnected efforts extend beyond science; they reflect cultural stewardship and community pride.

As Soria said, “Those who were once rulebreakers are now protectors.”

Each afternoon, members collect trash and ferry it to the mainland. BFAR Masbate, Samapusi, and the City Agriculture Office all claim to report zero illegal activity within the sanctuary in recent years.

Signs of life

Marine biodiversity has surged. According to BFAR’s Geralph Andrade, sightings now include shellfish, sea crabs, groupers, pelagic fish, and top predators like sharks, rays, and stingrays.

“Sharks are indicators of a healthy ecosystem,” Andrade explained. “If you see a big one, it means the reef is thriving. If there are none, something’s wrong.”

Once obscure, Buntod is now a tourism magnet often compared to the Maldives. It has earned national accolades, including Outstanding Marine Protected Area and Outstanding Locally-Managed MPA.

“Milestones have happened here,” said City Agriculturist Engr. Rodolfo Ajero Jr. “Buntod is now an icon of Masbate.”

More than a reef

Buntod’s rebirth reveals the power of local stewardship. But it wasn’t spontaneous; it was cultivated through trust, policy, and community grit.

Despite restored reefs and revived livelihoods, the deeper challenge lies ahead: shifting from isolated success stories to a movement where empowerment becomes the norm, not the exception.

In a province scarred by red-tagging and violence, Buntod asks: What if communities were empowered instead of cast aside? | Story by Mark Angelo Mallari, Gianne Paula Cadag, and Athena Grace Cedillo

Editor’s Note: This article references Jofer Asilum’s 2019 study on Masbate’s marine protected areas. Efforts to follow up with sources and assess recent developments are ongoing.

An earlier version of this report interchanged Barangay Tugbo in Masbate City with Barangay Tugbo in the Municipality of Mobo. This has since been corrected, and we apologize for the oversight.